Scaling Suki's Command Understanding: Building Fast and Accurate Intent Classification for Clinical Voice Assistants

At Suki, our mission is to reimagine the healthcare technology stack and lift the administrative burden from clinicians. Creating a best-in-class assistive voice-based clinical documentation solution requires solving complex natural language understanding challenges. As doctors increasingly rely on voice commands to interact with patient data, whether scheduling an X-ray, adding a diagnosis, or querying patient information, the need for fast, accurate command interpretation becomes critical.

In this blog post, we'll explore how we built a new intent classification and slot-filling system that enables Suki to understand natural clinical commands with high accuracy while maintaining sub-300ms response times, all while working with limited training data.

The Challenge: Understanding Clinical Voice Commands at Scale

Clinical voice commands present unique challenges that distinguish them from typical voice assistants. When a doctor says, "Schedule an X-ray for the patient with the chest pain complaint," our system needs to:

- Classify the intent (“scheduling a procedure” here)

- Extract relevant slots (procedure type: X-ray, patient identifier: chest pain complaint)

- Map to backend actions (specific API calls with structured parameters)

- Do it fast (under 300ms to maintain clinical workflow)

This became even more complex as Suki expanded its intent fleet to complex commands like Question and Answering from patient data and natural language editing (NLEditing) [1], where doctors expect increasingly natural interactions rather than rigid command structures.

The Core Problems

Limited Training Data: Unlike consumer applications, clinical voice commands don't have large public datasets. The specialized nature of medical terminology and clinical workflows means we needed to work with whatever proprietary data we had collected.

Speed Requirements: Clinical workflows demand real-time responses. LLM API calls, while accurate, introduce latency that disrupts the physician's focus on patient care. Cost is another factor that prevents us from using LLMs with the volume commands that Suki handles.

Natural Language Variability: Doctors don't, and shouldn’t be expected to, speak in structured commands. They might say "John mentioned some tingling in his left foot" instead of "Add left foot tingling to patient John Smith."

Scalability for New Commands: As Suki introduces new features, we need a system that can quickly adapt to new command types without extensive retraining or data collection.

Our Solution: A Two-Stage Approach with Smart Data Augmentation

We developed a dual-component system that addresses both intent classification and slot filling while maintaining the speed and accuracy requirements critical for clinical use.

Part 1: Intent Classification with Contrastive Learning

Rather than relying on traditional classification approaches, we built a retrieval-based system using sentence encoders and vector similarity.

Data Augmentation Strategy: We started with our existing command dataset and used synthetic data generation to expand our training examples. We used LLMs to scale this process up. This allowed us to create variations of clinical commands while maintaining semantic accuracy.

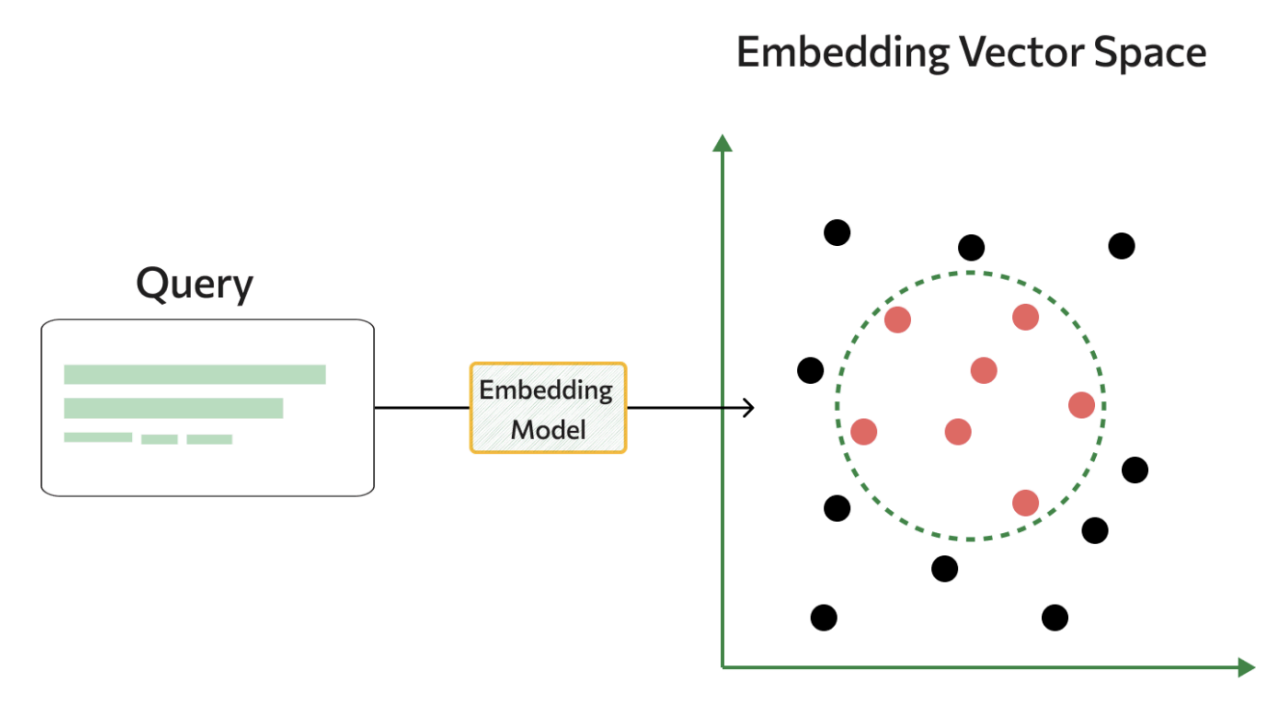

Vector Store Approach: We trained a sentence encoder to create embeddings for all our training queries and built a vector store that maps query embeddings to their ground truth intents and parameters. During inference, we encode the new query and use k-Nearest Neighbor voting with the most similar examples.

Online Contrastive Learning: Existing sentence encoders do not classify medical intents well, especially for Suki’s specific use cases. Therefore, finetuning was required, more specifically, a type of finetuning known as contrastive finetuning. Contrastive finetuning, as opposed to classification, learns to define a Euclidean space where semantically similar data points are close to each other, rather than focusing purely on classifying the correct command. This subtle shift in training has shown to be an effective tool for finetuning embedding models [2], especially with limited data. Empirically, we found online semi-hard triplet loss to be our most effective loss function. This approach automatically identifies hard and easy examples while training, helping the model learn to distinguish between similar but different clinical commands. For instance, "go to his HPI file" versus "move his HPI file here" might have similar embeddings initially, but contrastive learning helps the model separate these crucial distinctions.

This approach achieved 98% accuracy on real-world clinical voice data while supporting few-shot classification, due to the unique vector search inference pipeline.

Part 2: Slot Filling with Optimized Language Models

For slot extraction, we needed something more sophisticated than traditional Named Entity Recognition (NER), since doctors often speak in ways that require interpretation rather than direct extraction.

Flan T5 with LoRA: We fine-tuned Flan T5 using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) on our slot-filling dataset. This approach gave us the generative capabilities to handle cases like “the patient notes numbness in his right and left hands”, which maps to “numbness in hands”.

N-gram Caching for Speed: The challenge with autoregressive transformers is inference speed. Medical terminology often gets tokenized into long token sequences; a single medical term might require 12+ tokens. We developed an n-gram caching algorithm that leverages the fact that medical terms are often repeated and can be cached for faster retrieval.

Our caching strategy works by:

- Run a lightweight part-of-speech tagger over the entire sequence

- Maintaining a heuristic cache of common medical n-grams and part-of-speech n-grams

- Allowing the model to quickly select cached n-grams from the original input

- Running a final confidence check to reject tokens with low certainty scores

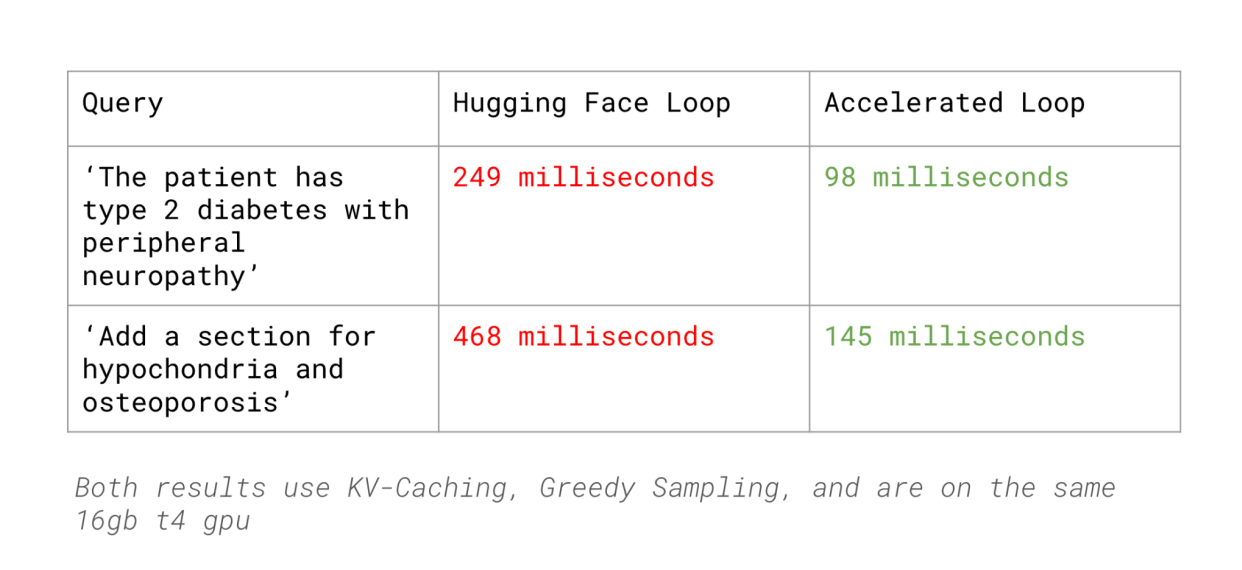

This approach reduced our slot filling latency by 62% compared to HuggingFace’s inference (with KV Caching, Greedy Sampling) while maintaining accuracy comparable to LLMs like GPT-4.

Results: Fast, Accurate, and Scalable

The complete system delivers impressive performance metrics:

- 98% accuracy on real-world clinical voice commands

- 133% latency reduction compared to GPT-4 baseline

- Sub-300ms response times maintaining clinical workflow requirements

- Few-shot learning capability: 90%+ accuracy with only 15 training samples for new command types

This last point is particularly important for Suki's product development. As we introduce new features and command types, we can quickly adapt our system without extensive data collection efforts.

Impact on Clinical Workflows

The improved intent classification system directly supports Suki's mission of creating an invisible and assistive clinical experience. Doctors can now:

- Use more natural language when interacting with patient data

- Trust that their voice commands will be interpreted correctly

- Experience seamless transitions between dictation and commands

- Benefit from new product features that rely on sophisticated language understanding

Looking Forward

This system represents a foundation for more advanced clinical voice understanding capabilities. As we continue expanding Suki Assistant’s skill set, particularly in areas like clinical Q&A and natural language editing, having fast, accurate intent classification becomes even more critical.

Building technology that truly assists clinicians requires solving complex technical challenges while never losing sight of the ultimate goal: helping doctors focus on what matters most, their patients.

Acknowledgments:

This was done as part of an internship at Suki AI, special thanks to Feroz Ahmad, Rohan Kalantri, and Gaurav Trivedi for their guidance on the project.

References:

[1] https://www.cnbc.com/2024/12/18/suki-google-cloud-expand-partnership-on-assistive-health-tech.html

[2] https://arxiv.org/pdf/2408.00690